by Matthew Robinson

Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

“When it most closely allies itself to Beauty: the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” - Edgar Allen Poe

In 1992, Carol J. Clover wrote about the horror genre’s division among the sexes with particular emphasis on the female victim and male murderer. Clover designated the woman survivor of these films "The Final Girl" and noted that the survivor often embodied a specific set of qualities, such as being chaste and of sound moral character. Has this notion of "The Final Girl" continued to persist in the horror genre today, 25 years later, or have new patterns begun to emerge?

Who is The Final Girl?

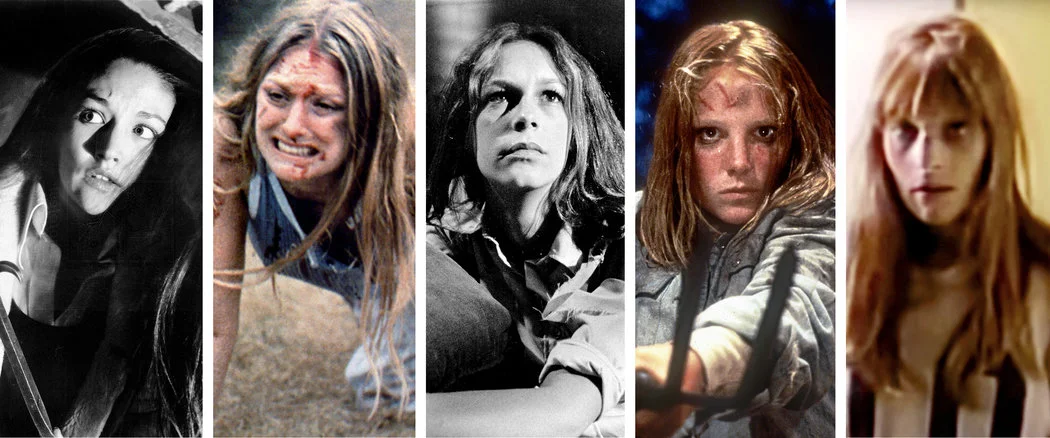

From left: Olivia Hussey in "Black Christmas"; Marilyn Burns in "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre"; Jamie Lee Curtis in "Halloween"; Amy Steel in "Friday the 13th, Part 2"; and Jan Jensen in "The Last Slumber Party."CreditFrom left: Bev Rockett/World Pictures Corporation/Warner Bros. Pictures, via Photofest; Bryanston Distributing Company, via Photofest; Trancas International Films/Anchor Bay Entertainment; Paramount Pictures, via Photofest; B. and S. Productions

As Clover outlined, The Final Girl carries a set of signifying qualities. She is an intelligent and levelheaded individual and is usually the first to sense that something wicked this way comes. The audience most closely relates to her character as both The Final Girl and viewers anticipate the horror that awaits them.

The Final Girl is pure, sexually inexperienced, and free of drug and alcohol use, vices that often lead other characters toward their deaths. The Final Girl may also lack gender-defining qualities and be, for example, a Tomboy, which allows for gender fluidity between The Final Girl and the audience. She may take on more masculine qualities as she seeks to defeat her villain, using phallic weapons such as a knife or machete to slay her demon. She is not a damsel in distress but a hero by the end of the film. She is someone that both male and female viewers can identify with and root for along the way.

Clover also urges viewers to approach the typical slasher film through a feminist lens. While the female heroin becomes masculine in her efforts to survive, the male killer thus becomes more feminine as the film unwinds. The viewer often learns that the killer has a stunted sexuality or physical anomaly, suggesting a damaged masculinity that ignites his desire to kill.

The Final Girl progressively transforms into a more masculine version of herself as she survives each encounter with the killer. This challenges the long-standing tradition of the male hero. But while the masculine qualities The Final Girl takes on are necessary for her survival, so is the need for her character to remain female to preserve the overall balance of the film.

The history of The Final Girl

It seems worthwhile to examine the horror genre up through the present day and highlight those films that continue to embody Clover’s theory of The Final Girl. The following examples trace the development of The Final Girl over time as well as the unique challenges The Final Girl presents to the male norm of heroism.

Leatherface and his chainsaw.

Clover regards Sally from Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) as the first major example of The Final Girl within the horror genre. Clover acknowledges that Marion Crane’s sister Lila in Psycho (1960) may be considered the inaugural instance of The Final Girl, but Lila is such a minor character that Sally seems a better model.

In Texas Chainsaw Massacre, a deranged family of ex-slaughterhouse workers terrorizes and kills Sally’s friends and brother before going on to torture Sally herself. Sally escapes and is chased by the chainsaw-wielding Leatherface along with another member, “the hitchhiker”, of the slaughterhouse family. Sally eventually reaches the highway and is saved by a passing semi-truck driver. The film ends with Leatherface swinging his chainsaw around in defeat.

Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis)

Laurie Strode from the Halloween (1978) series is a second example of a classic Final Girl. Laurie exemplifies the qualities Clover lays out in her theory: she’s a virginal Tomboy and is the only character to first notice and understand the villain’s, Michael Myers’s, motives. She successfully outwits Myers’s repeated attacks and survives.

Stretch and her chainsaw

The character Stretch in Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) symbolizes a unique turn in the horror genre. This turn is one of reflectivity as director Tobe Hooper openly addresses the gendered nature of the slasher flick. In the sequel, Leatherface and Chop Top terrorize a radio talkshow host. Although Stretch is not unsullied, she makes herself unavailable to suitors. At one point, Leatherface corners her in a radio station. With his chainsaw revving, Stretch begins to charm Leatherface, and Leatherface returns her seductiveness with grunting sounds of pleasure. As a result, Leatherface releases Stretch and in a sense protects her by leading Chop Top to believe that he has indeed killed her. At the film’s climax, a large explosion kills most of the family and only Chop Top survives. Stretch turns the tables on Chop Top by grabbing a chainsaw and slicing him in half. The film ends with Stretch waving her chainsaw around—a reference to the original film.

The way the two Chainsaw films end, Sally saved by a man and left screaming and then Stretch left yielding a chainsaw after saving herself, may be a mark as to the progressive nature of the horror genre and changes to the standard Final Girl formula.

Neve Campbell as Sydney Prescott in Scream (1996)

Sidney Prescott in Wes Craven’s semi-satirical slasher Scream (1996) bends Clover’s theory a bit as well. The film famously lays out the rules for surviving a slasher film: no drugs, no sex, and never say “I’ll be right back.” Sidney is atypical of the classic Final Girl in that she has sex with her boyfriend, a man who is later revealed to be one of the two killers in the film. Although Sidney breaks the no sex rule, her sexual experience is still morally sound because she is in a committed relationship with someone she loves. Although Scream updates and modernizes Clover’s theory, the moral code remains in tact with the audience.

Alex, The Final Girl in High Tension

Alexandre Aja’s High Tension (2003) throws an interesting curveball into the slasher genre by featuring a killer who first appears male but is later revealed to be female. The film unhinges Clover’s theory a bit more by suggesting that the female killer, Marie, is driven to kill out of mad love for The Final Girl, Alex. This gender swap surprise re-envisions the classic slasher model into something more contemporary and perhaps marks the beginning of the end for the slasher film.

Amber Heard is Mandy Lane

All the Boys Love Mandy Lane (2006) continues the reimagining of gendered horror roles. In this film, a hooded killer appears to adhere to classic slasher rules. For example, a young woman performs oral sex on a young man and is killed moments later. However, in the end the killer is revealed to be two people: one man and one woman, but the woman eventually proves to be the real killer between the two of them.

In both High Tension and Mandy Lane, the slasher film is flipped on its head. Females take on both the masculine survivor and masculine killer roles. These two films openly play with the audience’s expectation to see certain roles portrayed within specific gender molds. The reason both films feel like they have twist endings is because the audience never expects the killers to be women.

The slasher film seems to die off to some degree at this point in time. The waxing and waning of the popularity of sub-genres is normal, especially in horror. Mixed into the early 2000s are remakes of classic slasher flicks such as Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and Halloween. These remakes do little to change the classic formula and are not notable enough to spend time on here.

Today's Final Girl

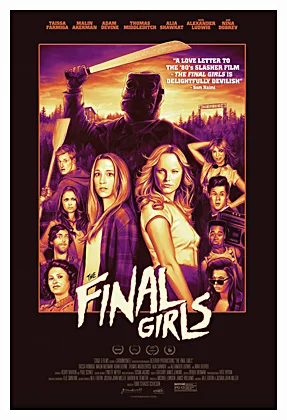

More recently, two films have emerged that are post-Final Girl: they have a self-reflective quality and comment directly on the essential qualities of The Final Girl. The Final Girls (2015) and Final Girl (2015) openly acknowledge Clover’s ideas.

In The Final Girls, the daughter of an actress from a famous slasher film called Camp Bloodbath gets sucked into the film itself. Since her mother died in a car accident, getting sucked into the film gives the girl a chance to reconnect with her mom. She tries to keep her mother virginal and alive in hopes of bringing her out of the film and back into the real world. She knows the rules, the idea of the Final Girl, and actively uses it to her advantage.

In Final Girl, a young woman is trained from a young age to go after a group of college boys who murder women. Again the film plays with the notion of a Final Girl as defined by Clover by having its main character aware of the rules. Curiously, both films uphold what all slashers tend to: the feminine transforms to the masculine to defeat the killer.

Where does the transformation of the horror film now place the idea of The Final Girl and Clover’s brilliant analysis of the slasher flick? The slasher film has become self-aware due in part to the aforementioned 2015 films. As the horror genre cycles through different trends—such as the haunted house and supernatural phenomenon—it is interesting to ponder when the classic slasher will regain popularity. Will it return to its roots or be reimagined into something new?

Clover herself was careful not to give too much credit to slashers for showcasing empowered female characters. Gendered roles still exist in horror films today, but it does seem like the genre has progressed. One can look at recent horror films such a Robert Eggers’s The Witch, Gerard Johnstone’s Housebound, or Dan Trachtenberg’s 10 Cloverfield Lane to find strong female characters that do not need to transform into masculine versions of themselves to overcome their villains. Instead, their femininity is viewed as the source of their strength.

The Final Girl may today be a thing of the past. Looking at the year ahead in horror, the paranormal theme still reigns supreme with Insidious Chapter 4, Annabelle 2, and Rings as forthcoming releases in 2017. If the slasher does come back, one must imagine that the gendered roles Clover uncovered in 1992 will continue to morph and evolve. Until then, The Final Girl seems to be lying dormant like a masked killer waiting for its next sequel. Clover’s theory will continue to stand as a useful looking glass with which to trace the transformation of the female as a poetic victim to an empowered, masculine individual capable of surviving so many of the horror genre’s greatest stories.